One of many unsuccessful things I’ve written is a novel. I mention it not because I want you to rush out and buy it. You can’t. It’s only available on kindle (that’s how unsuccessful it was. By the way, it’s called Crossword Ends in Violence (5)). I mention it because writing plot in a novel is much easier because you, the narrator, can flat out tell your readers all the information they need to know. You don’t have to worry about the screenwriter’s toughest, thorniest, deadliest foe: exposition.

In a sitcom script, you have only scene descriptions and dialogue. That’s it. You have to convey exposition and all relevant information using these tools whilst avoiding stupid lines like ‘So, tell me again, what are we trying to achieve here?’ or the ultimate script fail: ‘So how long have we been brothers?’

Some writers try and fix the latter with a stage direction which is ‘JOHN turns to PETE, his brother.’ Great. You’ve told the cast and crew these two guys are brothers. You haven’t told the audience. If they need to know they are brothers at this point, you’re going to need some dialogue or action that’s going to show this.

So here are eight tips on how to convey exposition without resorting to dreadful, creaky, crunchy lines where characters just say things that are necessary rather than natural. Actors sometimes spot them and ask, on set, ‘I don't understand this. Why is my character saying this? It doesn't feel like something they would say.’ If you’re answer is ‘We need to explain to the viewer x, y and z’ then you have failed as a writer on this occasion. Here’s how to avoid that:

1. See, Not Hear

It’s easy to assume that all information has to be delivered through dialogue. Film makers understand this more than sitcom-writers, as a rule. They worry about mis-en- scene and cinematography. It can sound ethereal and arty, but it’s all about story telling. You’re trying to convey information about a character. Why not move the scene to where that information is assumed? Do they have a prop that tells the story? Does the way they hold it tell that story even more? A man with a tool belt is clearly useful around the house. A man holding a hammer from the wrong end is clearly less useful, telling the audience this guy is not handy. It’s not just the locations, props, and costumes you use. It’s the way that you use them.

2. Gotta Love a Man in Uniform

Who is everyone? How do they relate to each other? What they’re wearing can explain an awful lot without a word of dialogue. One upside of military comedies – at least ones on television – is that they all wear uniforms which indicate rank. And even if we don’t know which rank slide means what, you can tell who’s in charge given who calls who ‘sir’ or, in the case of Bluestone 42, ‘boss’. And who snaps to attention when someone walks in.

This is essentially a development of ‘See, Not Hear’ but thinking about what the characters are wearing doesn’t always come naturally. So ask what your characters are wearing in each scene? Or the first time we meet them? What does it say about who they are – and how they relate to other characters? Do some people have to wear a uniform and others get to wear 'management-style' suits? Does someone wear their clothes inside out, or back to front, or refuse to wear the right thing? What they are

wearing says a great deal about where they’ve come from and, more importantly, where they’re going – both literally and figuratively.

3. Write a Joke

It’s a sitcom. A few decent jokes go a long way and cover a multitude of exposition. And there’s no better than Curtis & Elton on this. A certain Blackadder line could read:

George: Are we going to attack the enemy? How exciting!

Blackadder: Yes. And we’ll all die in the process. This war is a complete waste of time.

That’s exposition. And not funny. Here’s the same exposition with jokes:

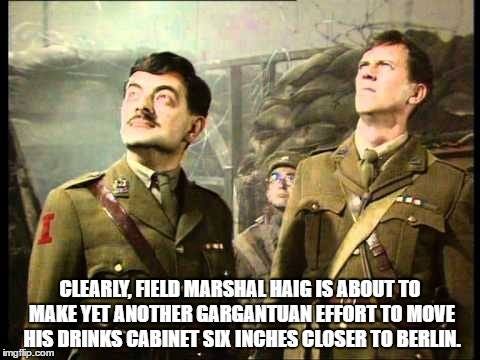

George: Great Scott sir, you mean, you mean the moment's finally arrived for us to give Harry Hun a darned good British style thrashing, six of the best, trousers down?

Blackadder: If you mean, "Are we all going to get killed?" Yes. Clearly, Field Marshal Haig is about to make yet another gargantuan effort to move his drinks cabinet six inches closer to Berlin.

Not only is the latter version 1000% funnier, it also gives us so much more information about their characters. We’re only four minutes into the series when these lines crop up and these are brand new characters for us, since the previous series was set a hundred years earlier where George was the Prince Regent and Blackadder was the butler. Now Blackadder is a Captain. And we know George, a lieutenant, is a lower rank because he calls Blackadder ‘sir’. We also learn in the few lines that George is insanely patriotic, overly optimistic and probably a bit thick given how previous attacks have gone. We learn that Captain Blackadder is a realist, cynical and unimpressed with the general directing the battles and their futility. This isn’t just exposition.

Clearly, the tone of Blackadder doesn’t suit every show, but a joke can really help. So cover some exposition by writing one. If you don’t want to write jokes, write a drama. But you’ll still have this exposition problem, so read on.

4. The Value of Supreme Idiocy

Blackadder is surrounded by idiots like Baldrick, Mrs Miggins, Prince George, General Melchett and Lord Percy. Idiots are very useful – partly because they are often joke machines. But another good reason to have an idiot-character in your show is because they can get the wrong end of the stick and then the other characters have to explain or clarify what’s going on to them, which will also clarify things nicely for the audience.

In Hut 33, my radio sitcom set in Bletchley Park during World War 2, I had a character called 3rd Lieutenant Joshua Fanshawe-Marshall, possibly the stupidest man on earth, brilliantly played by Alex Macqueen (above, centre). I did that because the process of codebreaking that actually took place in the huts at Bletchley is really hard to understand. So I needed a military person, not an intelligence person that would need things explained to him.

Joshua is a colossally stupid man who thinks that German language already is a code and the enemy should play fair and speak English. But Joshua also needs to know what’s going on because he’s sort of in charge, being the embarrassingly inept son of a gung-ho Patton-like British general. His idiocy, position and backstory all made him a character who needed stuff spelled out to him. This was very useful for explaining exposition – and generated jokes at the same time.

5. Have A Blazing Row

Your character is explaining a plan. The other characters listen. Boring. Annoying. Not funny. Could someone have an alternative plan? And explain their plan, or keep interrupting the original plan – and the two characters have an argument about it? Going back to Blackadder, Baldrick’s cunning plans are always really funny, and give our hero the chance to explain a decent plan, with jokes. Although sometimes, the plan isn’t even explained. It’s obvious. When Blackadder asks for two pencils and a pair of underpants, we’re intrigued – and then we go straight into seeing them in action (funny), and then the explanation. Which leads to asking:

6. Do you Need to Tell them this?

Backstory and exposition often seem very important when you’re planning a sitcom, or outlining an episode, but when it comes to writing it, you often realise you don’t need to explain yourself as much as you might think. This is especially the case with backstory.

Newer writers tend to get quite hung up on where the characters have been, and what they did before – but the audience are more interested in where they are going. Remember, The Vicar of Dibley turns up. She just arrives. No backstory. No past. She’s the new vicar. (As a church goer, this would never happen without consultation with the church PCC and wardens but that doesn’t really matter. Again, no explanation needed.) If you like, you can reveal backstory and hidden depths later.

7. Cheat

If you’ve still got a whole ton of exposition to crunch through, you might have to cheat. Cheating’s fine. Two of my favourite shows do it. Modern Family and Parks and Recreation have a very murky, ill-defined documentary style that is wildly inconsistent with odd looks to camera at various points. Somehow it doesn’t seem to matter. I don’t know why. It just doesn’t. I think they’re able to get away with this because the language and grammar of television has been heavily influenced by ‘Fly on the wall’ documentaries and reality TV in the last fifteen years, and then The Office.

You can cheat by having a narrator. This is how Arrested Development crunches through an amazing amount of story in such a short time. Ron Howard’s voiceover is never really explained but again, it doesn’t seem to matter. More cunning and less cheaty is the voiceover in Desperate Housewives who is a character speaking from beyond the grave. Nice move.

You can have a character talk directly to camera. Miranda does that, and it’s incredibly useful from a story point of view, as she can relate previous incidents in her life, announce the story of the week and give us a heads-up on foreseeable problems, which will hopefully lead to unforeseen ones. Miranda’s pieces to camera also give her an extremely deep connection with her audience.

8. Really Cheat

Finally, you can cheat in the most brazen way possible by having a character called Basil Exposition (as in Austin Powers). It was only on the third time of watching the movie that I got that joke.

Have we slain the beast of Boring Exposition?

Probably not, but we might have given it a bloody nose.

Next, let’s get back to those Hack Lines and work out a way of replacing them with better ones. If you can’t wait, you can get the whole book, Writing That Sitcom, as a PDF right now here. Or the audio version here.

Writing a sitcom script is hard, but it can be made easier. I’ve put together a comprehensive course that breaks it all down and will help you get from a basic idea to a completed sitcom script in twelve steps (and a few months). More information here: