You can get this audiobook/podcast into your podcast player by clicking on ‘Listen on’ and get a private RSS which can then be pasted into your player. Why not do that now? It’ll then appear there every week.

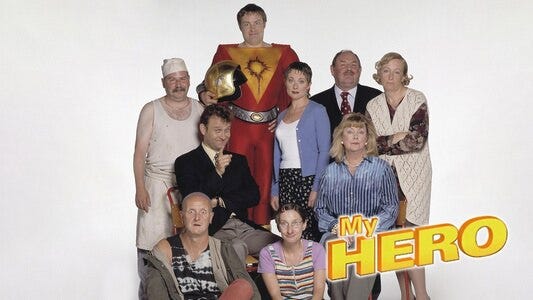

In the past, I wrote six episodes of a show called My Hero. I started writing episodes in the fourth series (2003), when it had ten regular characters. Yes, ten. The focus was always on the ‘hero’, played by Ardal O’Hanlon, who drove the main plot every week. His story would often involve his wife, Janet (Emily Joyce) and/or his venal friend, Arnie and/or his insane neighbour, Tyler. There was a B-plot, usually based around the slimy doctor (Hugh Dennis) and the psychopathic receptionist Mrs Raven (Geraldine McNulty), and a C-plot, often based around Janet’s snobby mum and long-suffering, cowardly dad.

It was a large cast to handle and the rule was that every character was in every episode. The upside was that you had ten different attitudes to any given situation – and therefore ten types of joke. There were lots of possible stories and starting points – which is why there are dozens of episodes (51, to be precise). And it meant that you didn’t need as many guests parts, since lots of roles could be filled by regulars (Janet’s mum could turn her hand to being a florist, for example, or sing in a choir; Mrs Raven could turn out to be very good at butchery and so on). And the audience would always rather see the regular characters than guests stars. Those are the upsides.

The downside was making sure enough people had enough lines, and jokes – and an attitude in every scene. You wanted to avoid that moment when an actor wondered why their character was in a particular scene and the honest answer was that they didn’t have enough to do, so you bunged them into a scene.

Servicing all these ten characters was hard work – but you always knew it was possible, because every week, we just about managed it.

The Set Up

The character make-up of My Hero was not of my choosing. The show was conceived by a delightful man called Paul Mendelson and I was invited to write on the show. And since money was offered, I accepted.

The show I’ve been writing more recently, Bluestone 42, was of my choosing, but Richard Hurst and I felt the characters had to reflect military reality. When we chose a bomb disposal expert as a lead character in a sitcom, we discovered that his team would be a minimum of four people: Ammunition Technical Officer (the bomb guy), Number 2, Bleep and Military Escort. We ended up with six in the team: ATO, Number 2, Bleep and a three man military escort – to give us an array of perspectives and rivalries, plus an interpreter, a padre, a Lieutenant Colonel. That’s nine characters – which, again, is very tricky.

We loved all our characters dearly and giving them good jokes and a satisfying story in 28 minutes is really hard work. Somehow, the stories seem to follow the same pattern as My Hero. Captain Nick Medhurst is ‘the hero’ and leads the main story every week, which normally involves one of the other characters. Mac and Rocket, the squaddies, tend to have a B or C plot, and the other characters are normally involved in the plot that’s left.

So, maybe Nick has a problem with his new number two, Towerblock – and turns to the Lieutenant Colonel for sage advice – that’s the A Plot. Meanwhile Bird has a running battle with Mary the padre over something – that’s the B Plot. And Simon’s being pestered by Mac and Rocket over something. That’s the C Plot, which may end up being almost the same size as the B Plot.

Sitcoms can support large casts. Some recent gems that come to mind would be Parks and Recreation and Arrested Development. Much older shows would be Dad’s Army and The Phil Silvers Show (aka Bilko). In each case, the show has a clear lead, eg. Leslie Nope in Parks and Rec, Michael Bluth in Arrested Development, or Bilko in The Phil Silvers Show – or a central relationship, like in Dad’s Army, between Mainwairing and Wilson.

It’s worth looking at those David Croft sitcoms which all had large casts, but a fairly clear central hub. Hi-De-Hi seemed to focus around a few central characters (Gladys, Ted and Spike, from memory) and draw in peripheral ones when needed. Allo Allo was centred on René Artois (or his ‘twin brother’) who was the ringmaster in a circus of lunatics, including his wife, her suitor, his mother-in-law, waiting staff, Nazis, members of the French resistance, British Airmen and an amorous Italian. But we never got lost because we knew that René was at the centre of it.

Keeping Focus

Based on all of the above, I would suggest that you ultimately know who your show is about and fill it accordingly.

Your show should be about one key character (eg. Miranda, David Brent, Mrs Brown, Basil Fawlty, Victor Meldrew, Wolfy Smith, Leslie Nope) or a central relationship (eg. Edina & Saffy, Rodney & Del Boy, Hacker & Sir Humphrey, Sharon & Tracey, Terry & June, Fletcher & Godber).

If you know this, you’ll know where your main A plots are coming from. If you don’t, you’ll have split focus, you’ll not know what you’re writing and the audience, should it make it that far, won’t know what or whom they’re watching. And ultimately, that character, or relationship, should encapsulate what the show is about.

There are always exceptions, of course. One would be Modern Family, which has a large cast and seems to split its focus equally between the three family units with no clear ‘star’ or ‘hero’. Each episode is normally three plots that run alongside each other. But then again, we should not be surprised at this. Modern Family is always exceptional. And maybe there was a clearer focus when the show started out, but, as we shall see, sitcoms take on a life and logic of their own once they’re up and running.

Avoiding Overlap

Whatever you decide, however many characters you end up with, central or peripheral, you need to make sure that all your characters have clear, contrasting voices and unique perspectives. If they are all given the same task (eg taking part in a Secret Santa or running a pub quiz), they should all instinctively go about it in completely different ways. When some news breaks (eg. There’s no hot water or there’s a hurricane coming), they all react in different ways, and then end up in conflict.

Quite often, I find, when you’re story-lining a new show, brainstorming ideas for plots, some characters generate stories and seem to end up in the thick of the action, and other characters you thought were going to be funny or useful fall by the wayside. This tells you something. You might not need that character. The character may have been critical in previous versions of the show. Maybe that character is your voice, but seems oddly silent or unfunny now the other characters are firing on all cylinders. Cut the character. It’s all part of the process, which is one of the reasons why developing new sitcoms take ages.

More next time. If you just can’t wait - you don’t need to! You can get the whole book, Writing That Sitcom, as a PDF right now here. Or the audio version here.

Or you might want to do my complete video course, which you can have a look at over here: